50 years of Ankur: Revisiting Ankur on the 50th anniversary of the classic

5 min read

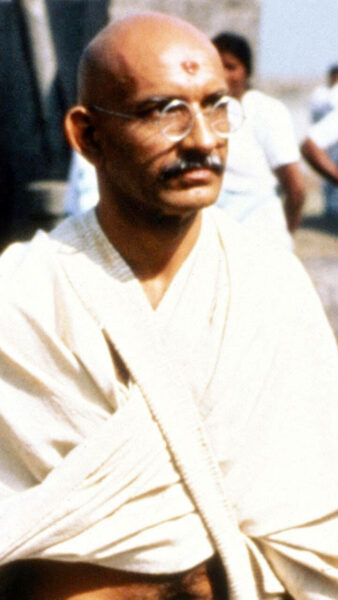

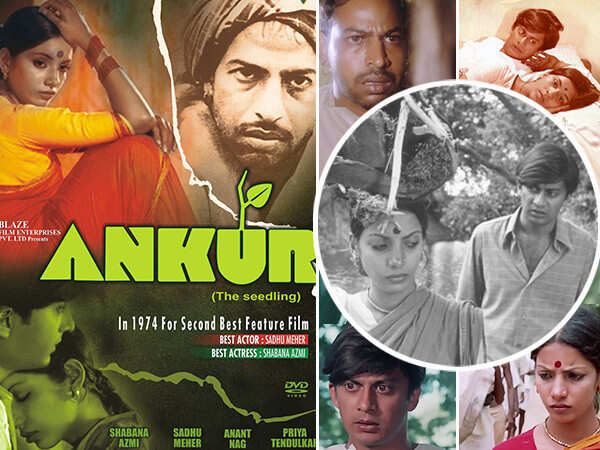

We talk about pan-Indian films currently but 50 years ago, Shyam Benegal made Ankur (1974), in Hindi, set the film in the rural areas of Hyderabad, and cast Kannada actor Anant Nag and Shabana Azmi as the main leads. The film marked the debut of Anant Nag and Shabana Azmi, as well as Priya Tendulkar. Shabana went on to win the National Film Award for Best Actress for it. It’s said that Shabana wasn’t the first choice for Benegal for the role. He thought she looked too sophisticated and beautiful to play a village girl. However, the first time actress defied all expectations and gave a powerhouse performance that’s taught at film schools today. It was a path-breaking film which redefined the landscape of art cinema in India. It also marked Shyam Benegal’s debut as a director. One can’t believe that such a layered film was made by a first time director. Some consider it Benegal’s finest work, and that’s saying something, considering his gloried repertoire. He won the National Film Award for Second Best Feature Film for Ankur.

Unlike his famous cousin Guru Dutt, Benegal never sought relevance in commercial cinema. Ankur, written by him, (with dialogue by Satyadev Dubey) is said to be based on actual accounts. On the most basic level, it’s a tale of oppression by the upper caste towards the dalits in a village. Surya (Anant Nag), though educated in a modern city, reverts back to feudal norms, making life difficult for the villagers just because he can do so. He’s the landlord’s son after all. His affair with Lakshmi (Shabana Azmi) stems from the fact that he has watched his father take a second wife. In fact, the second wife has more status in the village as she was gifted the best piece of land by his father. His first act of cruelty is to cut the water supply to her lands as an act of revenge. He shares a difficult relationship with his father (Mirza Qadir Ali Baig). They are never shown as seeing eye-to-eye. One feels he has always resented his father’s lifestyle. So it’s highly ironic that he goes on to make worse mistakes than his father. And while his father is quite open about his own affair, Surya is shown to be a coward and shuns all relations when the going gets tough.

The film subtly points out the rampant casteism which existed then and which still exists today. Seemingly nothing has changed, even after 50 years. The villagers grumble more about a lower caste girl making food for an upper caste man than about her affair with him. When Saru (Priya Tendulkar), Surya’s wife, first enters the household, she’s shocked by it. She refuses to drink tea made by Lakshmi as she’s from a lower caste. She knows about the affair and unlike Surya’s long suffering mother, doesn’t tolerate it and wants to get rid of Lakshmi. She’s blinded by envy when she learns Lakshmi is pregnant and makes sure that she leaves her household.

Ankur goes on to examine our sexual drives quite candidly and without offering judgements. Surya has an affair with Lakshmi because he’s married to a girl who is yet to attain puberty. Another character Rajamma has an affair as she wants a child. Her need mirrors that of Lakshmi, who too wants to bear a child and has an affair with Surya partially because of this need. Ankur means seed in Hindi, and that’s the primary motif of the film. The desire to get impregnated might have led Lakshmi to stray. Though it could also mean the seed of revolution. At the end of the film, a village boy, who always had an amicable relationship with Surya, is shown throwing a stone at one of the window’s of Surya’s house and running away, implying that a spark against the atrocities of the upper classes has been ignited.

It’s also a love story. Despite being deaf and mute Kishtayya (Sadhu Meher) loves his wife Lakshmi (Shabana Azmi). They get along despite his handicap. It’s this love which reforms him of his alcoholism and makes him come back to her. He even forgives her for her infidelity. He gets brutally whipped by Surya and that proves to be the breaking point for Lakshmi, who disowns whatever feelings she has to Surya and publicly curses him, and takes her husband home to nurse him. Sadhu Meher won the National Film Award for Best Actor for his role. He managed to move the viewers despite not having any dialogue and that’s saying something. He’s a lost gem who never got his due in Hindi cinema.

The film, which is known for its stark and realistic camerawork, also marked the beginning of an association between Benegal and his DOP Govind Nihalani. The latter began his career as a cinematographer in Ankur and went on to collaborate on many films with Benegal, notable among them being Nishant (1975), Manthan (1976), Bhumika (1977), Kondura (1978) and Junoon (1979). He branched out on his own as a director later on with Aakrosh (1980).

Another mainstay was editor Bhanudas Divakar, who too opened his innings with this film and went to become a constant in Benegal’s films. He won the Filmfare Award for Benegal’s Junoon.

Benegal, along with Shabana, went to become one of the mainstays to parallel art cinema in India. But their first collaboration together will always get talked about. The film hasn’t lost its relevance and remains highly watchable. The alcoholism, poverty, casteism, communalism, political unrest which the film portrays are universal issues which haven’t gone away. The filmmaker gave us a story about tangled human relationships and wove these issues around them. By the by, despite being branded as an art film, the film made money at the box office. The film’s producer, Lalit M. Bijlani, who produced the film for just five lakhs rupees, went on to make one crore with its release. The film’s commercial success paved the way for Benegal being financed by individual producers, as well as government corporations like Gujarat Milk Co-Op Marketing Federation Ltd, Association of Corporations and Apex Societies of Handloom, and NFDC throughout his career.Ankur subtly points out the rampant casteism which existed then and which still exists today. Continue reading …Read More