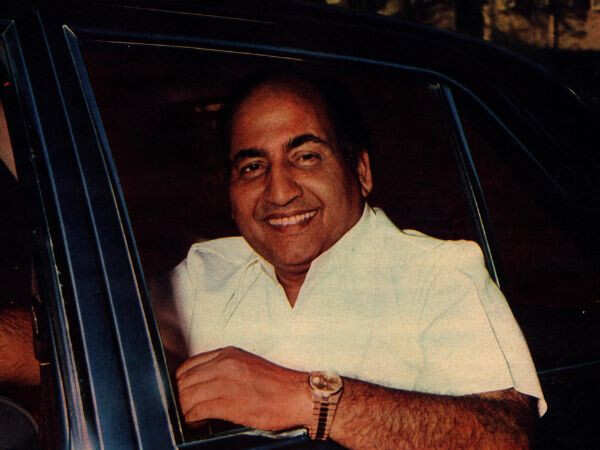

Throwback: A rare Mohammed Rafi interview from 1979

6 min read

This year marks legendary singer Mohammed Rafi’s 100th birth anniversary (he was born in Punjab on December 24, 1924) and on this special occasion, Filmfare brings you a rare interview with the late singer. In this interview, which was first published in the Filmfare magazine in 1979, Rafi talks to AA Khatib about the then changing landscape of Hindi film music. Rafi also reveals why his children did not follow in his footsteps and become singers. He also reveals his opinion on losing out to Kishore Kumar once Rajesh Khanna’s Aradhana became a superhit and the Rajesh-Kishore partnership became a mainstay of films. Read on…

Rafi has been the darling of four generations of film music composers ranging from Shyam Sunder to Rajesh Roshan, and has recorded, at a rough estimate, over 26,000 songs. He lives in an imposing two-storey mansion amid quiet surroundings at Bandra. “Rafi Villa” is protected by high compound walls and two watchmen keep round-the-clock guard at the gate. The exterior of the mansion is oil-painted in white and dark-green, the symbol of Islam.

It’s cool and peaceful inside the house, not many people live there and they all speak in whispers. We are led into a massive drawing room which has sliding glass doors; wall-to-wall carpeting, glass-top tables, shelves full of trophies handed over at jubilee functions. Rafi’s six Filmfare trophies are displayed prominently on a tree-shaped structure. The wooden cupboards with glass shutters are full of gramophone discs — some 18,000.

Rafi’s brother-in-law Zahir, his companion, adviser and secretary all rolled into one, is around. Rafi always had the reputation of being a simple, soft-spoken and kindly man and some people in the industry accuse Zahir of spoiling Rafi’s reputation. “Yes, they call me names,” Zahir says, “but people in this industry are very shrewd, some are even crooks, and Rafi saab can be easily cheated. Once when I was not in town, he did a recording for a producer, Rafi saab trusted the producer and didn’t count the money he was paid. At home we discovered that the man had paid half the money he was supposed to pay.”

Enter Rafi, dressed in his usual bush-shirt and trousers. He says, “Asalam walaikum!” and sits. He isn’t too well, suffering from an attack of flu. He asks if the interview can be split into two sessions. He has cancelled all recordings for a week. He begins to talk about the past.

His ascent began with one of his first songs Watan ki raah mein from Shaheed (1948), under composer Ghulam Haider, followed by the ever-popular duet with Noorjehan from Jugnu (1947) (Yahan badla wafa ka…) composed by Feroze Nizami. Probably his most memorable song is Bapu ki amar kahani for the popular duo Husnalal-Bhagatram.

Rafi, now 55, has been a darling of four generation of film music composers ranging from Shyam Sunder to Rajesh Roshan. His career graph took a steep upward rise and remained steady except for an inexplicable dip around 1972, but the singer has since rallied remarkably.

None of his sons followed his father’s profession. He explains: “They are all fond of music, my son Khalid and daughter Nasreen had good voices and talent for singing but I never encouraged them because I have a certain status as a singer, and I didn’t want any of them to take it up and not do it well.”

He recalls his early life. “When I was 14, I ran away from home and landed in Lahore, which was a film centre. My elder brother knew that noted singer Ustad Khan Abdul Wahid Khan and I had my first lessons in music under him, and a couple of years later, under Ustad Bade Ghulam Ali Khan.

“In Lahore music director Shyam Sunder gave me the first chance to sing a film song. It was a duet with Zeenat Begum in a Punjabi film titled Gul Baloch. I was thrilled. In Bombay Ghulam Haider gave me a break in Shaheed. It was the famous song. Watan ki raah mein… It was a seven-minute song and in the first part I led Khan Mastana, and in the second part, he led me. I became known with this song.”

He continues, “Yet Feroze Nizami was hesitant to give me a chance in Jugnu. Noorjehan then graciously stepped in and persuaded Nizami to give me a try. She went out of her way to do any number of rehearsals.”

His career suffered a setback for three years from 1972. “I was away from Bombay for a long time,” he points out. “Secondly, Aradhana (1969) had become a super-hit. All the songs were popular—two were sung by me, the rest were by Kishore. It also marked Rajesh’s rise to super-stardom, and he decided that from then on all his songs would be sung by Kishore. He was a big star and producers and composers had to agree.”

There is, Rafi agrees, “dirty politics” in film music, but he denies that he has knowingly harmed the chances of any new singer. “I was a newcomer myself once, and I know the struggle one undergoes to come up. But I also believe that if you have outstanding talent, just nobody can deny you your rightful place. When I came in there were Khan Mastana and Durrani, but I proved my worth. I know nobody could have stopped me from achieving what I have achieved today. So the new singers need not develop any complexes about senior singers.” He added, “There are just a handful of top composers and each one has a number of films. Now there is so much pressure on them to turn out songs that they have no time to sit with new singers, rehearse them and then record the song. It may take hours. But with an experienced singer—well, I take just about 20 minutes to rehearse and complete the recording in two or three hours.”

He adds, “And then the producer invariably tells the composer not to take a chance with new singers, that in any case, he is paying for the singers and he would like to have the best. Over and above this the leading man insists on having his songs sung by a particular singer. It’s a vicious circle and it’s no use blaming singers for not allowing new people to come up.”

Rafi however doesn’t think that any of the new singers, male or female are outstandingly talented. He agrees that the standard of film music has been steadily deteriorating. “Film music used to be based on classical and light classical music once because composers had a classical training. And then they were conscientious. They had enough time to work on their tunes.” Today’s film music is more business than art. Now the trend seems to be to grab as many films as one can and lift a catchy tune from here, and another from there and adapt them. Tell me, where’s the time for a composer to work on the songs when he has 20 and 30 films on hand and has to turn out songs like a conveyor belt? Their songs may be instant hits but aren’t great compositions. They don’t grow on listeners like those composed by Khemchand Prakash, Ghulam Haider, Naushad, SD Burman, Madan Mohan, Shanker-Jaikishen.” Among today’s composers, he mentions Laxmikant & Pyarelal as people who know their jobs.

Rafi finds useful diversion from the monotonous routine of Bombay in his concerts abroad. “It’s pleasure cum business, I can see other countries of the world, meet people and I have the opportunity to visit my children in London.” The first concert was in 1960 to East Africa. Now Rafi goes on his concerts twice a year and has covered almost the entire world, barring China, Russia and Pakistan.

This year marks legendary singer Mohammed Rafi’s 100th birth anniversary. Continue reading …Read More