Mrs Review: Hindi Remake Of The Great Indian Kitchen Hits Home

5 min read

Mrs Review: Sanya Malhotra lives the role and director Arati Kadav orchestrates her resources with striking efficiency.

Home is where the hurt is for the titular protagonist of Mrs., a Hindi-language remake of The Great Indian Kitchen. Sanya Malhotra lives the role and director Arati Kadav orchestrates her resources with striking efficiency. The result: Mrs. gets as close to being a home run as a replication of a critically acclaimed, widely viewed film still fresh in public memory can be.

Mrs. makes several significant and clear deviations. The cooking area in the film, for instance, isn’t exactly like the straggly, perpetually damp kitchen in the Malayalam film. Though far less spacious, it is brighter, more airy, and less dispiriting. But the plight of the married woman consigned to this corner of the hearth is no less pitiable.

A kitchen sink leaks. The problem remains unattended for days. The lady’s repeated plea to her doctor-husband to summon a plumber falls on deaf ears. The worsening situation isn’t a mere functional crisis – it also points to the state of a disintegrating marriage.

The dirty water from the sink that accumulates in a bucket is just as much a metaphor for the grind of domestic chores that patriarchy foists upon women.

Arati Kadav’s pointed, if a tad window-dressed, the film is close in spirit to The Great Indian Kitchen. It is imaginatively crafted – faithful but not slavish. Although shorn significantly of the compellingly and unsettlingly raw edge of the original, the Jio Studios and Baweja Studios production streaming on Zee5 makes its point forcefully enough not to be a wasted adaptation.

The writers – Anu Singh Choudhary, Harman Baweja, and Kadav – use hand-me-downs from Jeo Baby’s original screenplay and blend them, with varying results and a few new elements. Much of what is germane to this film springs from its relocation to urban North India.

While the tapioca-to-wheat cultural transposition yields some fresh detailing, the narrative canvas is palpably eviscerated of some of the deeper socio-religious layers of a source material that was rooted in a very clearly defined milieu. The location in Mrs. appears somewhat indeterminate. It constitutes a backdrop that seems steeped in a generalised ethos.

It is not so much the particulars of the setting as her husband’s presumptions about gender roles that overtly determine what the newly-married Richa, an accomplished dancer relegated to the kitchen to cook and clean for her husband Diwakar (Nishant Dahiya) and father-in-law (Kanwaljit Singh), faces.

Nothing in the film, however, parallels the complexities inherent in The Great Indian Kitchen (especially those stemming from a Supreme Court ruling granting women the freedom to visit Sabarimala).

The family that Richa is married into owns a nursing home. The husband (a modest schoolteacher in the original) is a wealthy, workaholic gynaecologist. The man comes across as agreeable and mild-mannered until his ways begin to reveal his true sexist colours.

Diwakar does not tire of harping on how hard he works and how exhausted he is at the end of the day. His calling might suggest that he possesses a clinical understanding of women but his sexual relationship with his wife never goes beyond the strictly mechanical. That, of course, is only one of many ills that creep into Richa’s life.

Moreover, it isn’t the men alone who paint Richa into a corner. Her mother-in-law (Aparna Ghoshal), always affable, expects her to be adept at cooking and taking care of the home the way that she is. And when the frustrated young lady complains to her own mother (Mrinal Kulkarni), she receives little support. Get used to it, she is advised.

The relentless demands that the men make on the female protagonist in the two films are obviously similar in nature. The specifics are not. For one, dosa, puttu, kappa and black tea with cardamom are replaced by roti, halwa, biryani and shikanji.

No matter what the men, including a cousin (Varun Badola) who comes calling and does his bit to complicate matters, and the women – among them is an aunt (Lovleen Mishra) who swings by and enforces a strict Karwa Chauth regimen – throw at her, Richa has to take everything in her stride.

Nor is that all. There is a whole daily pile of other demands, seemingly innocuous but painfully incremental. The husband wants rotis right off the tawa. The father-in-law, a senior citizen of apparently gentle disposition, insists that all spices be ground by hand and that biryani be cooked dum pukht style, layer by layer.

Richa, caught in a perpetual cycle of insensitive impositions, has no say. She hopes to find a job and escape the rut. But the husband (through indirect means) and his dad (without mincing words) look for ways to stall her plans.

Like it did in The Great Indian Kitchen, the camera (DOP: Pratham Mehta) hovers constantly over food laid out on the dining table where father and son eat, generally in utter silence, oblivious of the toil of the women of the house to ensure they get their meals on time and to their taste.

Every dish that Richa cooks, every meal that she puts together and every chore that she performs – cutting vegetables, kneading flour, grinding spices, washing utensils and cleaning the kitchen – is an onerous test.

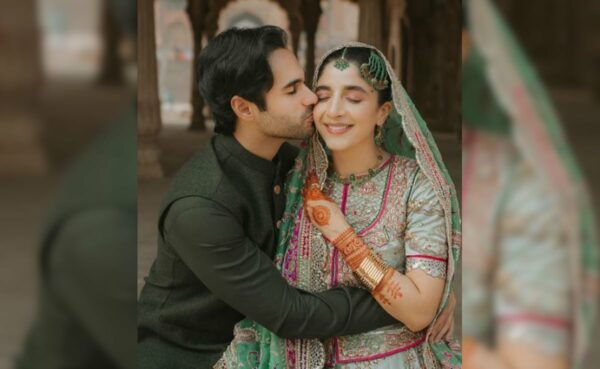

The director delivers in some interesting touches that are worth a mention. In an early scene, when Diwakar’s family visits Richa’s parental home ahead of their marriage, the two retreat to the terrace for a heart-to-heart, as couples invariably do in Hindi films about matchmaking and matrimony. It is obviously a red herring. Mrs. is nothing like an average marital drama.

Kadav, who debuted as a director with the remarkably inventive sci-fi fantasy Cargo, brings up the concept of prime numbers – indivisible except by themselves and 1 – to evoke the power of women. The thrust of the message is intact and it is delivered with clarity of vision.

The story that Kadav relates is, however, cling-wrapped with the sort of surface gloss that the original film steadfastly shunned in order to heighten the drudgery of the married life of a young woman crushed under housework.

In conclusion, to reiterate a question that is inevitable every time a Hindi remake of a recent South Indian film comes along, who needs a reworking of a story that is available on an OTT platform? To Kadav’s credit, Mrs. is more than a reproduction. It has a distinct soul.

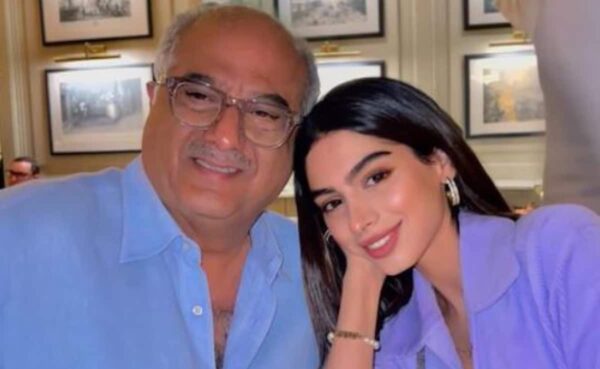

A fair bit of the credit for that should accrue to Sanya Malhotra. She hits home in a stinky kitchen sink drama. She exudes an affecting mix of vulnerability, bafflement, alienation and assertion, creating a discomfiting portrait of a woman trapped. Her intrinsic influence on the film helps the director make the exercise count.